FEMICIDE in Nederlands

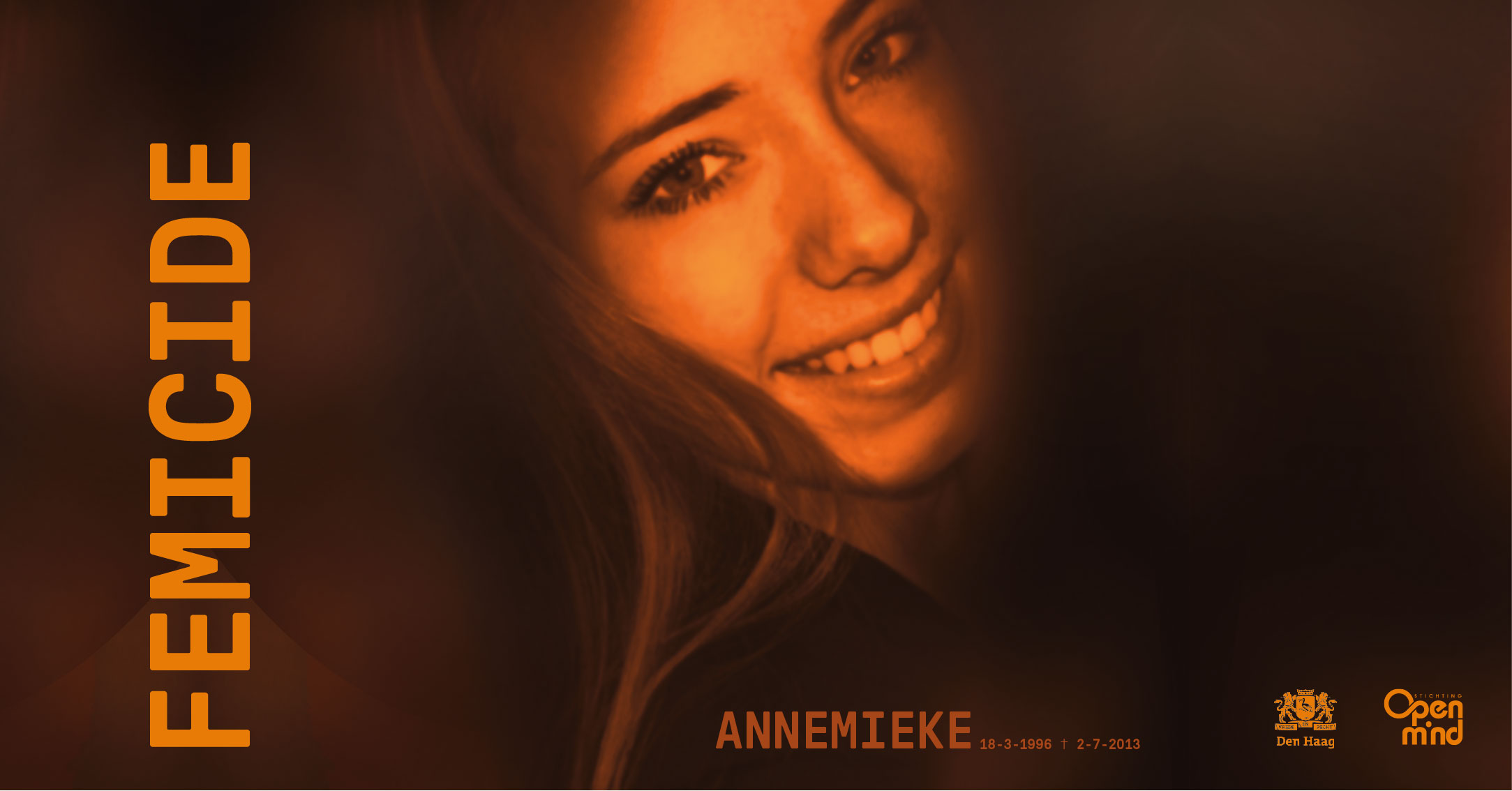

Every day in the EU, at least 2 women are murdered by an intimate partner or relative. Women are disproportionately more likely to be killed by their (ex-)partner or a relative than men. The exhibition FEMICIDE alerts, informs and gives a voice to victims of deadly (ex-)partner violence against women and a voice to their relatives. Read all the portraits and stories.

“We can no longer save her, we can still tell our story

and warn other women about femicide.”

Femicide is more than lethal (ex-)partner violence, it is also murder of a woman because of her gender, in other words because of the fact that she goes through life as a woman and is seen as property. This vulnerability is rooted in the unequal power balance between men and women. Women are more at risk of violence than men. In Europe, half of women have experienced sexual harassment, 1 in 5 of these experienced physical and/or sexual violence by a partner or friend. Statements like, “If I can’t have you, no one can have you” are typical and alarming in this.

Femicide knows no origin, social class or religion. The victims have nothing in common except something essential; they are women. The perpetrators are almost always men. Femicide is the most serious form of violence against girls and women and an unacceptable violation of human rights.

Gender-based feminicide is often not characterised in the media as femicide or murder, but rather referred to as ‘family drama’, ‘relational violence’ and ‘crime of passion’. These designations give the impression of unique cases that take place in the private sphere. However, this leaves out the violent pattern and gender-related motives underlying these murders. By not designating this murder as femicide, the horror of it, the fact that someone was murdered because she is a woman, is not recognised. This often results in poor registration, lower sentences and extra pain for the bereaved, on top of the great grief that is already there.

FEMICIDE is a project of the Open mind foundation, in cooperation with the municipality of The Hague and co-sponsored by: Federatie Nabestaanden Geweldslachtoffers – Programme Violence Does Not Belong at Home.

View the red flags and tips here, and for support with femicide in Europe.

RED FLAGS

Which red flags – even in cases of intimate terror – can indicate escalation of violence or even a fatal outcome?

- Stalking

- Threat of death (towards victim or the children or threat of suicide)

- Possession or use of weapons

- Recent violent behaviour

- Violence during pregnancy

- Forced sex

- Withholding of care that acutely threatens health

- Attempted strangulation, suffocation or drowning

- Extreme fear in the victim that her life or that of the children is in danger

- Victim dares not speak near partner and/or shows fear of partner

- Increasing escalation of severity and/or frequency of violence

It is confirmed from multiple studies: the motive for partner homicide appears to be mostly fear of being abandoned by the victim, followed by viewing the victim as ‘property’. These red flags are especially important to recognise in combination with additional factors: personality problems, possessiveness and control drive, jealousy as an expression of possessiveness, substance use (drink and drugs) and stress factors such as unemployment, financial stress and/or psychological stress.

What you need to know.

- Women, men and children can be victims of intimate terror. Know that gender plays a role in coercion and control: women are more likely to be victims.

- Intimate terror occurs in all walks of life.

- Do not be guided by first impressions and your own preferences. In intimate terror, one person involved may appear calm and pleasant, another confused and erratic.

- Intimate terror is unilateral, but may involve resistance by the victim. In cases of violence by both partners, do not be too quick to think “where two fight, two are to blame”.

- Intimate terror does not always have to involve physical violence.

- The impact on children is significant. In intimate terror, children themselves are also often belittled, coerced or controlled by the perpetrator.

Characteristics

In intimate terror, the characteristics often occur in combination:

At the start of the relationship, attempts are made to entrap the victim and entice her to move in together or marry at an accelerated pace. A controlling partner will try to cut off their partner from friends and family or limit contact with them so that you don’t get the support you need, for example by:

- suggest shared phone and social media accounts for convenience;

- holding off contact with family;

- giving false information or making up lies about the partner to others;

- monitoring all phone conversations with family and friends and cutting the line if anyone tries to intervene;

- convincing the partner that her family does not care about her and does not want to talk to her;

- block social media channels, delete accounts.

Compulsive monitoring can also manifest itself by:

- Fitting the house (e.g., bedroom and bathroom as well) with cameras or recording devices, sometimes using two-way surveillance to speak to partners at home during the day.

- tracking devices on mobile phone or in car (to determine location, for example), with or without the partner’s knowledge;

- for example, shaming on social media, (secretly or otherwise) checking search behaviour, mails on the internet and social media (for example, there are apps that allow you to break into WhatsApp unseen), catfishing (drawing up a false profile by one’s own partner in order to, for example, accuse the partner of infidelity);

- This also focuses on the message of control towards the victim. Humiliation thereby becomes part of what is already a clear boundary violation.

This may manifest itself in:

Restricting freedom of movement:

- not allowing you to go to work or school;

- restricting access to transport;

- monitoring all movements outside the house;

- gaining access to the partner’s mobile phone (and passwords, for example).

It can also manifest itself through total control over activities in the home situation, for example the time of eating to the manner in which toilet paper should hang.

Reinforcement of traditional gender roles

Making sharp distinctions between male-female roles in the relationship can lay a claim on breadwinning to thereby force the partner to provide cleaning, cooking and childcare.

Financial control

Controlling finances is a way of limiting one’s freedom and ability to leave the relationship. Financial control can be done by, among other things:

– making little money available, barely enough for essential items such as food or clothing;

– restricting access to bank accounts;

– hiding financial resources;

– preventing the partner from having cards or credit cards;

– closely monitoring spending.

Control over health and body

Coercive control can also apply to how much the partner eats, sleeps or spends time in the bathroom. For example, the partner may be required to count calories after every meal or to adhere to a strict exercise regime or which -or how much- medication may be taken, mandatory medication taking for non-existent disorder, and whether the partner is allowed to see the doctor.

The perpetrator aims to mentally distress the victim. The perpetrator tries to achieve this by casting doubt on the victim’s own sanity. The perpetrator will flatly deny reality, or claim the exact opposite of statements they have previously made. They will manipulate, lie to get their way and convince you that you are wrong.

Malicious remarks, abusive language and frequent criticism are all forms of bullying behaviour aimed at undermining self-esteem. This leaves the victim with the perception of being unimportant and inadequate.

Jealousy can be an expression of coercive control. For example, complaining about the amount of time spent with family and friends, both online and offline. This is a way of winding down and minimising contact with the outside world, by making the victim feel guilty. Also, the perpetrator may blackmail their partner, forcing them to do or refrain from doing actions.

A perpetrator of intimate terror may turn children against their partner by telling them that the other is a bad parent or by belittling the partner in front of the children, which may increase the victim’s sense of powerlessness.

– Bystanders, family, friends are used in actions against the partner. For example, in spreading rumours and gossip, in rejecting or shaming the partner. They can be used to enable contact with the partner.

– Think here of lawsuits, (false) reports to Veilig Thuis or police, influencing GP, school doctor, coach or teacher or management of school, neighbours and work.

This can manifest itself through, for example, demands made on the frequency of sex or actions during sex. For example, there may be coercive requests to take sexual photographs or videos

or being refused to wear a condom. The partner gets the message that she has to conform to his demands and wishes as otherwise there may be dire consequences.

If physical, emotional or financial threats do not work sufficiently, attempts can be made to control the partner by using children or pets. For example, by:

- threatening to harm themselves;

- making violent threats against the children;

- threatening to call youth protection to report that the partner is neglecting or abusing her children when this is not the case;

- intimidate the partner by threatening to make important decisions about the children without her consent;

- threatening to kidnap or kill the children

- threatening to get rid of or harm the pet.

Know: intimate terror – often – does not stop when the relationship is broken off!

After the breakup of the relationship, the terror can continue through, for example, stalking or deployment of many legal proceedings. The very act of breaking off the relationship can lead to escalation!

TIPS

Tips from survivors to break gender-based violence

For the victim

– Recognise the signals/red flags – also see red flag board in the exhibition

– Trust your intuition if it doesn’t feel right, take action

– Talk about it with someone you trust

– Don’t try to help him yourself, leave that to professionals

– Gather people around you that you trust, before breaking the circle

– Find a safe address, call 112 (EU) or 999 (UK) if you are unsafe

– Get out, make a report and never withdraw your report, otherwise the police cannot help you

– Don’t fall for fancy promises, they are often temporary

– A feeling of independence helps to step out of the circle

– Talk to fellow sufferers for greater understanding, recognition and acknowledgement

– If you want to break off the relationship, don’t do it alone and do it in a public place

– Say it officially; I am breaking up the relationship

– Do not be persuaded to have a final talk and never go to such a final ‘meeting’ alone

For professionals

– Read and recognise the signals/red flags

– Ask the right questions and dare to ask further questions

– Make an assessment of what help the next of kin need

– Work from the heart and show that you are also human

– Speak to both the child and the adults, each separately

– Take the perception of the child and their environment into account

– Always be alert to what may be going on behind the front door

– A sustainable solution occurs when everyone gets the right attention

– Look more at the child instead of mainly listening to the narrating mother

– Provide a person who facilitates contact with different organisations

– Ensure open and transparent communication with next of kin

– Involve the social environment in your plan of action (family, neighbours, school, work, caretaker and others)

For the bystander

– Read and recognise the signs/red flags

– Take that first step, however small, it can have big consequences

– Ask how things are going and if there is anything you can do to help

– Make it known that you want to support someone and stay in touch

– Be neutral, listen without judging

– If you suspect something, always try to make contact

– Keep listening and give space, especially do not exert pressure

– Believe what you hear and show it, trust someone

– If you see something that does not feel right, make an anonymous report to Veilig Thuis 0800-2000

– Listen to that gut feeling and start a conversation.

– Drop in spontaneously and visit her at unexpected times

Society

– Teach children that women are equal to men

– Never trivialise violence, take it seriously and take action

Doing nothing is not an option

SUPPORT

Victim of Violence

Emergency Number | Europe 112 (+31 592 348 112) | England (+44) 999

Bystanders and Relatives

Europe 116 006 helplines offer victims of a crime a listening and caring ear when they need it the most | England (+44) 08 08 16 89 111

For more information

EIGE | European Institute for Gender Equality

EIGE | Providing justice to victims of femicide: country factsheets