For the exhibition IN CONVERSATION, thirteen duos talked to each other. Duos of whom others might not immediately think they seek each other out. Central to each conversation is the terrible attack by Hamas on 7 October 2023, Israel’s atrocities in Palestine in the period thereafter and the violence in Amsterdam in November 2024. How can we as Amsterdammers stay connected, especially when the city is under pressure?

See and read the portraits and stories of Achraf & Micha, Noa & Oumaima, Salwa & Mirjam, Sliman & Erella, Itay & Sheher, Jelle & Sohbi, Chantal & Radi, Zohar & Volkert, Dana & Tamar, Taghreed & Maurits, Oudail & Nati, Shamier & Awraham en Neomi & Anisa.

The duo portraits were made by Miriam Guttmann, Jewish Amsterdam photographer and documentary filmmaker. The interviews were led and transcribed by Salwa van der Gaag, journalist with a Palestinian father.

IN CONVERSATION – to share the feeling of powerlessness

Noa (24) & Oumaima (22) founded Share the Dove with two other young people after 7 October 2023 – the day Hamas attacked Israel. An initiative to counter anti-Semitism and Islamophobia.

Noa: ‘How come we don’t talk to each other here anymore? Everyone is so caught up in their own world. Once I was waiting for the tram in Amsterdam and a woman came and sat next to me. I took out my earplugs to see what would happen. We got talking and then we sat opposite each other in the tram. We chatted about all sorts of things. Then I thought: why don’t we do this more often? It’s so easy. It almost feels unsafe to talk to each other, when in fact it creates more safety.’

Oumaima: ‘It seems illegal to make eye contact with each other. We have become such an individualistic society that we have lost it to care for each other.’

‘With Share the Dove, we go to all sorts of places, visiting schools and companies to open the way to conversation. We tell our story. When we start, we always say that we are very hard to offend. You can say anything, but I’m going to ask you why you say that and why you think that.’

Noa: ‘As long as it is done with respect. People often find it complicated to engage in conversation with people whose opinions they think are different. Then they prefer to cut it off.We also hear this from teachers, who say that you are not allowed to say certain things in class. Whereas you should actually ask the question: why are you saying that?Where does that come from?’

‘Having genuine interest in each other is very important.Try to understand how it is for the other person, how they feel.Without always trying to convince the other person that you are right.A conversation and a debate are very close to each other in the Netherlands.When people stop talking to each other, you no longer speak of a society.It is much easier to have prejudices about the ‘other’ than to listen to each other.’

Oumaima: ‘Muslim hatred is part of being Muslim. In this I recognise a lot in Jews, but I also see differences.We sweep it away, put it under the carpet. We don’t want to talk about it too much.It’s different with Jews.Both have advantages and disadvantages.You can say anything, but I’m going to ask you why you say that and why you think that.’

Noa: ‘I also think that’s because you feel that nothing will be done about it anyway. We both feel that we have to fight for our right to exist, that has to do with our background. Since 7 October 2023, I feel a lot of sadness and it is precisely with Oumaima that I find support.

We share the feeling of powerlessness.’

Oumaima: ‘My family is from Morocco, but we see the Islamic world as one body.If one part is in pain, we feel it in our whole body. It is pure happiness where you are born, you have to be aware of that.’

Noa: ‘It is the same in Judaism.We think every human life is worth the same amount.And people should stop thinking that if you have a certain background, you automatically stand for something.In the Netherlands, I don’t support the current cabinet’s plans either, but I am a proud Dutch woman.’

IN CONVERSATION – to experience the real connection

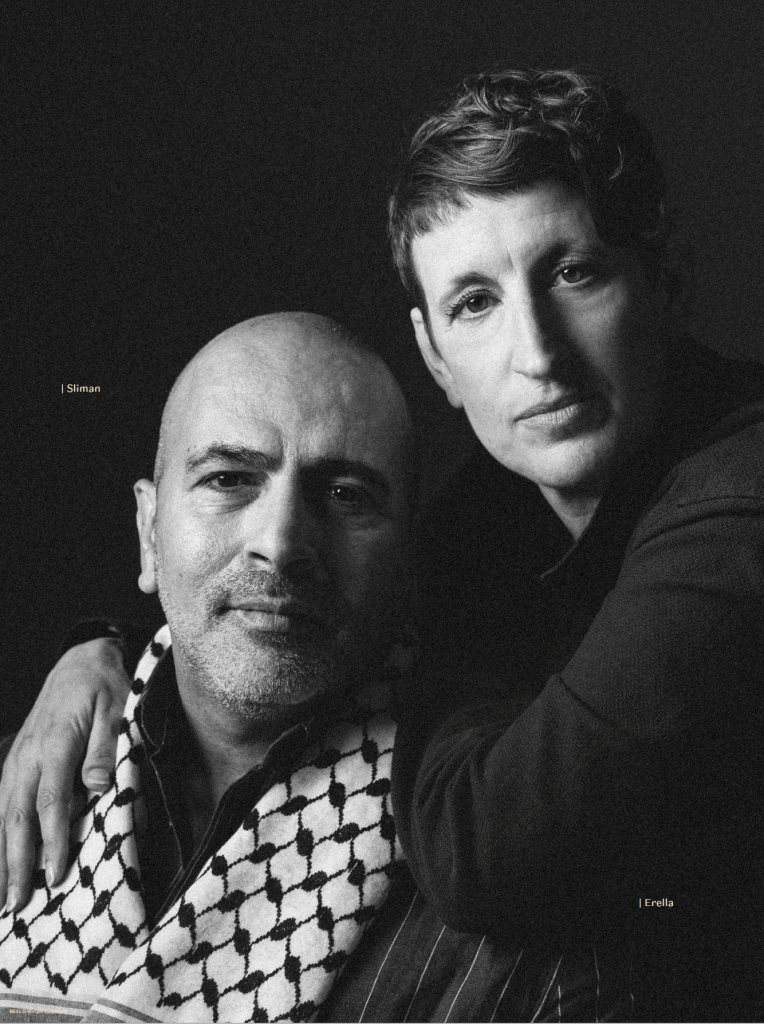

Erella is Jewish and was born in Israel, she grew up both there and in the Netherlands. Her father and his family still live there. Together with friends, she founded Gate48, a platform for critical Israelis in the Netherlands. Sliman is Palestinian and was also born in Israel. He has already lost 19 family members in Gaza since 7 October 2023. He himself has now lived in Amsterdam for more than 20 years.

Sliman: ‘I grew up in a Jewish neighbourhood in a city in Israel and I always believed that things can be different, that we can live together peacefully. I learned that dehumanisation can never be good and that the promise ‘this must never happen again’ must apply to everyone.’

‘My father was 9 years old when his family was expelled from their home in the city of Jaffa during the Nakba in 1948, when the state of Israel was founded. He often took us along the route he walked then. He told us in detail how that had happened. Only later did I realise that was his way of processing his post-trauma.’

‘There is a river of hate flowing through the country and that river is flowing very hard. I have always tried to be a stone in that river, so that when more and more join it, they eventually form an island with which to build a bridge between the two sides. Together with people like Erella. I still believe in that.’

Erella: ‘Yes, so do I but it is very difficult because as a stone in the river, you have to go through every but it is very difficult because you are pushed away like a stone in the river by everyone and everything. Any critical voice is opposed and if you say anything critical of the Israeli state, you are put down as a traitor.’

Sliman: ‘For me, it is very easy to talk to Erella. If you feel that the other person feels your pain and tries to understand you, you can move forward together.’

Erella: ‘The basis has to be right, that has nothing to do with whether you are Jewish or Muslim. It’s about whether you have common values. That you fight together against the genocide that is now taking place in Gaza. People are now acting as if Muslims and Jews are opposed to each other, but that is pertinently untrue. This is not about religion at all.’

Sliman: ‘It is easy to say we stand for human rights, but it is about our actions. I often wonder if we are really doing everything we can against the genocide going on in Gaza. We can only really say we have learnt from our history if we apply the promise ‘this must never happen again’ to everyone.’

Erella: ‘Many people dare not speak out because they are afraid of being called anti-Semites. We really need to stop that. I also find it offensive because this is about me as a Jewish person. My identity is used to flatten a conversation when they don’t know how I feel. For example, I feel much more connected with Sliman, a Palestinian who comes from the same region and with whom I share values, than with someone who has completely different political views from me, but who also happens to be Jewish.’

‘Amsterdam is a diverse city so then we should also show that everyone is welcome here. We have to stop distinguishing between groups every time. Our connection is a real connection, not just to set a ‘good example.’

IN CONVERSATION – To first name the real problem together

Jelle (36) is a Jewish Amsterdammer. Palestinian Sobhi (39) was born in Nazareth, he has now lived in the Netherlands for 10 years.

Sobhi: ‘My whole family still lives in Palestine and Israel. I didn’t understand what racism was until I started travelling outside Israel. Only when you see another reality do you understand what is wrong with the one you live in. Like my mother, who, when she calls me when I’m on the bus, is still afraid that an Israeli will hear me speaking Arabic and do something to me. While I now live in Amsterdam.’

‘It’s hard to be here while they are there, but emotionally I can’t quite grasp it. I know I worry about their safety, but I don’t really feel it. I think that is a way of coping. As a Palestinian, you understand very early on: you are not safe. Not because of your values, but because you are Palestinian. You are treated as a second-class citizen everywhere.’

‘My father told me not to talk about what happens there, not to post anything on social media. Some Palestinians lost their jobs or were sent to jail. I also paid a price by speaking out, I lost my job, but I can’t stay silent. It goes against my nature. I have no choice but to speak out against genocide and for equality.’

Jelle: ‘I converted to Judaism when I was 20. My father has a Jewish background and I have always felt strongly connected to that identity. The past year has been very difficult for me, being Jewish suddenly feels very fraught.’

‘There are horrible crimes happening, in my opinion, supposedly in ‘our name’, supposedly for ‘our safety’. I feel abused and lied to. Large parts of my community don’t seem to see how damaging that is. I think it is very important to show that there is a big difference between Judaism and the state of Israel. Because it is always pretended that you are an anti-Semite if you stand up for the Palestinians, it creates confusion. That’s what Israeli leaders want, but also our politics are abusing it now. And that drives people apart. Fortunately, I see more and more Jews around me who now also understand this and are speaking out against Israel’s actions.’

Sobhi: ‘It is totally ridiculous to think that you create security by bombing Gaza, by killing children. There can only be more hatred created that way. In addition, I find it disturbing that some Dutch people are fine with the superiority of Israelis over Palestinians and the total dehumanisation of Palestinians. Because of this, you can feel the hatred here now too.’

‘I initially found this kind of project superficial. Of course a Palestinian and a Jew can talk to each other. It’s not about that. It’s about unjust systems. The power dynamics and system give one more power over the other.’

Jelle: ‘I agree with that. You have to name the real problem first. But projects like this are important to counter a dangerous us/side narrative.’

IN CONVERSATION – to counter polarisation

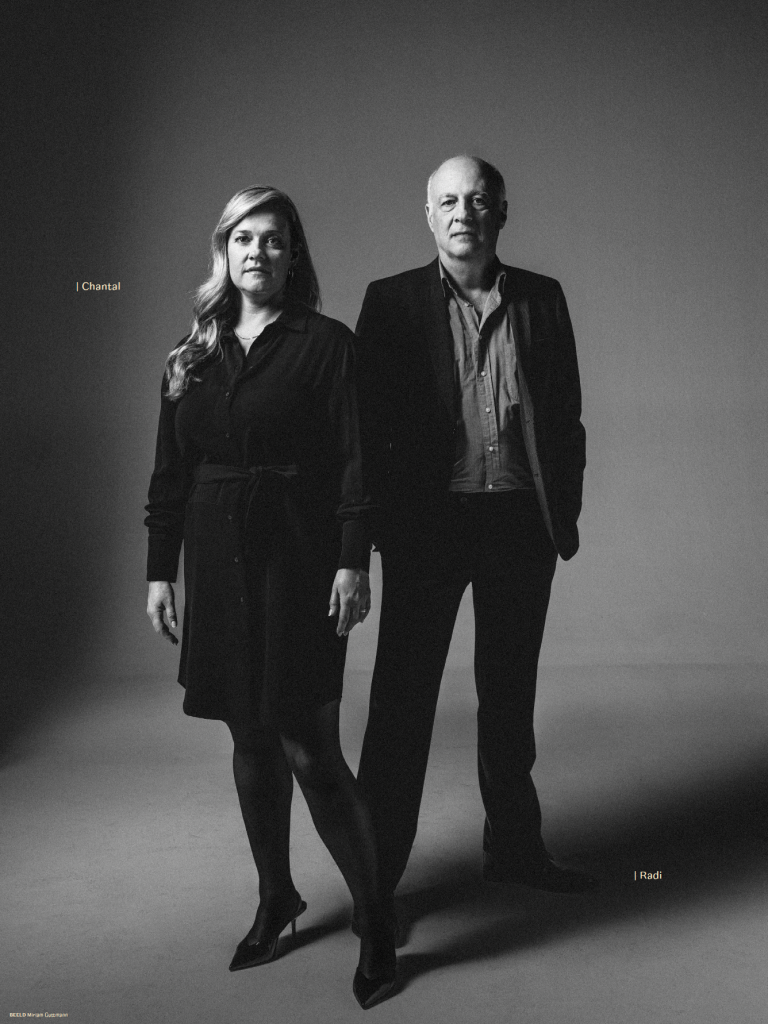

Chantal (44) is Jewish and has been working for years to bring Jews, Muslims, Israelis and Palestinians together. Radi (67) is half Dutch and half Palestinian and does no different. Both firmly believe that seeking connection is the only solution against growing hatred.

Radi: ‘Over the years, I have heard many stories from Jewish Dutch people about the war. And I’m still shocked every time. Losing loved ones in a mass murder, as happened to your family and almost all other Jewish families in this country at the time, is terrible.’

‘My father was born in the Old City of Jerusalem and grew up in Ramallah. He moved to England in 1946 to work for the BBC. Two years later, the state of Israel was founded. That was traumatic for my father. He lost the country, the society and the Jerusalem he knew. Losing your loved ones in war is already hard to imagine, but an entire society?’

‘He was always angry and frustrated when it came to Israel and the Palestinians. I admired his drive, but I also saw that it poisons your life if you can’t give a place to the injustice done to you.’

Chantal: ‘Then you literally get sick, that goes into your body. I’ve been trying to connect Jews and Muslims for over 20 years. I do that to avoid becoming embittered. Otherwise you get caught up in the whirlpool of misery. That is sometimes very tempting, and sometimes I want to cry and be angry, but it serves no purpose. In the end, I am looking for something constructive.’

‘I find black-and-white thinking – especially in the context of my own family history – terrifying. Hating each other harder here won’t help anyone. My parents are children of war, which is why I find it so terrible to see what is happening now, because this works on for generations to come.’

‘My grandmother was in five different camps and narrowly survived. Everyone around her was gassed. And yet she said to me: ‘dear, in every population you have good and bad people.’ If this woman can go through all this and then still have a heart full of compassion, I cannot help but do what I am doing now. That is my example.’

‘Segregation is increasing and if we stop speaking to each other, then it will be the end because dehumanisation will occur. I always say: you have to imagine that the person you are facing is your son or daughter. What would you want for that person then?’

Radi: ‘I agree with that. By speaking out, we counter polarisation. In our own circle in Amsterdam, on social media or in the newspaper. Even if it is emotionally exhausting, because it is. It is worse for the Palestinians than I have ever experienced and there seems to be no end in sight. Emotions play high as a result, including in me. I think dismay and sadness at what is happening to Palestinians in Gaza is justified. But you don’t save any Palestinian child with racism or violence against Amsterdam Jews. And violence, even if you disagree with each other politically, is always unacceptable in a democracy like ours anyway. On that common ground, we should still be able to find each other in this country and in this city it seems to me.’

Chantal: ‘I like that about you, that deep-rooted responsibility. It is especially important to keep talking now. After all, the greatest enemy remains not hatred but indifference. I recognise that responsibility. A piece of practical idealism for a better future.’

Radi: ‘Not even a better future, a better present.’

Chantal: ‘Amen.’

IN CONVERSATION – to learn from each other’s grandparents’ stories

Tamar (28) – a Jewish Amsterdam native – and Dana (24) – a Palestinian Amsterdam native – know each other from so-called liaison dinners. Since Hamas’ attack on Israel on 7 October 2023 and the bombing of Gaza, Tamar has been organising them with her sister to bring Amsterdam Jews and Palestinians together.

Tamar: ‘I have always felt safe in Amsterdam, but the November 2024 violence had an impact. It was the first time I saw anti-Semitism happening like this in Amsterdam. At the same time, I don’t want to be used as a pawn by a right-wing government. I don’t feel safer putting away the Islamic community as scum, supposedly to ‘protect’ the Jewish community. They are playing us as minorities against each other. Both Muslim hatred and anti-Semitism are on the rise because of this.’

Dana: ‘I too am shocked by the events in Amsterdam. On the contrary, I felt really free in this city for the first time. I spent my first years of life in Jerusalem. But there, there is a lot I am not allowed and I always have to be on my guard. As a girl of 12, I was searched by Israeli soldiers because they thought I was carrying a bomb. I had a pink suitcase with pink clothes and I was checked for three hours. Just to humiliate me.’

‘It is nice that we get to know each other better during the dinners you organise. By sharing personal stories with each other, you learn to see each other as human beings. On 7 October 2023, my world collapsed. I have lived through many wars, but this was different. The people killed on that day, the hostages taken. I don’t do it justice by saying it breaks my heart. What Israel has been doing in Gaza since then, all the people who were killed, there are no words for that.’

Tamar: ‘At the liaison dinners, where Jewish Amsterdammers, Israelis, and Palestinians come together, we learn from each other’s grandparents’ stories. Dana’s grandparents survived the Nakba (the formation of the state of Israel in which Palestinians were driven from their homes and murdered, ed.). I discovered how both our grandparents experienced some form of expulsion and oppression. In my family, it was often about the Holocaust. My grandparents survived, but much of my family was murdered. It was special how we grew closer by sharing these stories – which shaped us as grandchildren – with each other.’

‘Creating hatred and polarisation is easy, but I very much want to be a face for nuance, connection, understanding, humanity. The way I care about my family is the same as how you care about your family. I love in a similar way as you do. One life is not worth more than another. We must not succumb to the extremism that Hamas and Netanyahu are so keen to take us into, we must hold on to our shared humanity.’

Dana: ‘Polarisation is always portrayed as something extremely negative because it is so tearful. But that doesn’t mean you always have to agree. It’s precisely the diversity of perspectives that I find so beautiful. The conclusion is not that you can’t have different opinions, the conclusion is that you have to listen to each other.’

‘I always try to understand where something comes from. What do you achieve by putting away someone else’s pain? Can’t we just acknowledge that your family went through something painful and so did mine? It’s not a competition.’

IN CONVERSATION – even if you disagree

Oudail (28) came to the Netherlands from Lebanon when he was 13 years old. Nati (26) was born in Israel but came to the Netherlands when he was two months old. During the conversation, they soon find out that they come from completely different worlds and that connecting with each other is difficult. Something they both remain open to, though.

Oudail: ‘We came to the Netherlands because of the war with Israel. Always with the idea of going back, but we still live here. By now I have a life here. However, it is a constant search how I relate to my roots in Lebanon and to my life in the Netherlands.’

Nati: ‘That is recognisable. I grew up in the Netherlands, but almost my entire family lives in Israel. I come from an Orthodox Jewish family. On 7 October 2023, I was in Israel, sleeping when suddenly the air alarm went off. The days that followed were very tough. I wanted to bring food to soldiers, but my parents wouldn’t let me.’

‘Since then, I have been increasingly affected by anti-Semitism. Several times, especially in the past year, I have been harassed and even threatened on the streets because I am Jewish.’

Oudail: ‘I came to this conversation with an open mind, even though I find it difficult to talk to you about this. I want to put myself in your shoes and I want to listen to you. But that you want to give food to soldiers who kill so many in Gaza is really going too far for me.’

Nati: ‘The soldiers are protecting me and my family, but that doesn’t mean I don’t think what is happening in Gaza is terrible. I have no words for it, but Israel should be allowed to protect its citizens.’

‘I see it differently from you. We were given different perspectives from childhood. We both heard certain stories. Only from one side. It is difficult to totally turn your worldview around in one conversation. For me, it is very intense that people are openly calling for the destruction of my country and people.’

‘Ideally, I want everyone to be able to live in peace, there will be no casualties on either side and everyone will be able to develop.’

Oudail: ‘Something is needed for that. What Israel is doing now is disproportionate. I think it is good that the Palestinians are being talked about more in the past year, but I still notice too often that what Israel does is justified. Responsibility has to be taken.’

Nati: ‘I do understand that you find it fierce that I said I would give food to soldiers. I would also find it vehement if you said you would bring food to Hamas. For me, soldiers are the people who protect me and my family. For me, it’s not about killing the Palestinians, it’s about my own fear.’

Oudail: ‘The way you see the Israeli army, some people think Hamas is a resistance movement, protecting Palestinians from the occupier and oppressor Israel. Ideally, I would like the violence from both sides to stop and there to be a solution so that Palestinians and Jews can live side by side.’

Nati: ‘I hope by having this kind of conversation, we try to understand, accept and respect each other’s pain. It’s a kind of wall that needs to come down. I would like to look at topics that do connect us, like our religions, for example.’

Oudail: ‘I am also open to connecting even if we don’t agree with each other. You and I are both here and we are not going anywhere. We have to live together. I think the municipality of Amsterdam also plays a big role in this, it has to set a good example.’

Nati: ‘And commit to dialogue. The biggest danger is that we no longer treat each other as human beings.’

IN CONVERSATION – to counter dehumanisation

Volkert’s (46) Dutch father and Palestinian mother met during his holiday, they married and started living together in the Netherlands. That is where Volkert was born. Zohar (40) comes from a Romanian Jewish family from Israel. He lives and works in the Netherlands.

Zohar: ‘I grew up in Israel without knowing a single Palestinian. I only met one when I joined the army and had to guard a small settlement. When you grow up in Israel you learn that you are Jewish and that you are a Zionist. You just have no idea yet what that means.’

‘The narrative you are taught: the Palestinians are the enemy and they want us dead. You hear of terrorist bombings they committed and heroic stories of Israelis who saved people. You learn that you have to defend yourself.’

‘Only later did I discover that Palestinians are also just people, eating breakfast in the morning and loving their neighbours. Nobody wakes up in the morning and thinks: how will I finish off this other group of people?’

Volkert: ‘That you think so badly about other people can only come about if you never speak to each other. That’s why segregation is so dangerous. Then there is room for dehumanisation. And when dehumanisation arises, the most terrible things can happen. That is much more difficult when you look each other in the eye.’

‘My mother was always concerned with what was happening in her homeland. I got her anger and sadness and took over. I was always very concerned about the Palestinians. My mother got cancer and passed away in 2007. Since then, things have been different for me. When she was sick, she no longer had the energy to be so concerned. It also took away my energy. And it’s hard because it’s been going on for so long and it seems so hopeless. Incidentally, that doesn’t mean I accept the injustice now.’

Zohar: ‘I was preoccupied with other things, in my work seeking a solution to poverty in the world, for example. But at one point I found that so hypocritical of myself. Why should I focus on that when there are such big problems in my own country? Close to the house where I grew up are people who do not have equal rights as us. Since I no longer live in Israel, I see that much more and feel the obligation to speak out about it.’

‘I am sorry that with the arrival of the Maccabi supporters, the peace in our peaceful city was disturbed. But we must be careful not to get carried away by big words and political interests now. I am convinced that in Amsterdam we can still live well with people of all backgrounds. Of course, I cannot deny people’s feelings and it is true that there has been violence, but the city has not suddenly become more unsafe.’

Volkert: ‘I’m glad you say that, because that’s how I feel too. What happened after the violence did frighten me. Violent things were said that only increase hatred. We really have to be careful with that. You just talked about a narrative being instilled in you, that danger is also lurking here. But fortunately, there are enough people with common sense who say: this is not what we stand for. This is not our city. The people of Amsterdam are much more nuanced than that.’

IN CONVERSATION – to share grief with each other

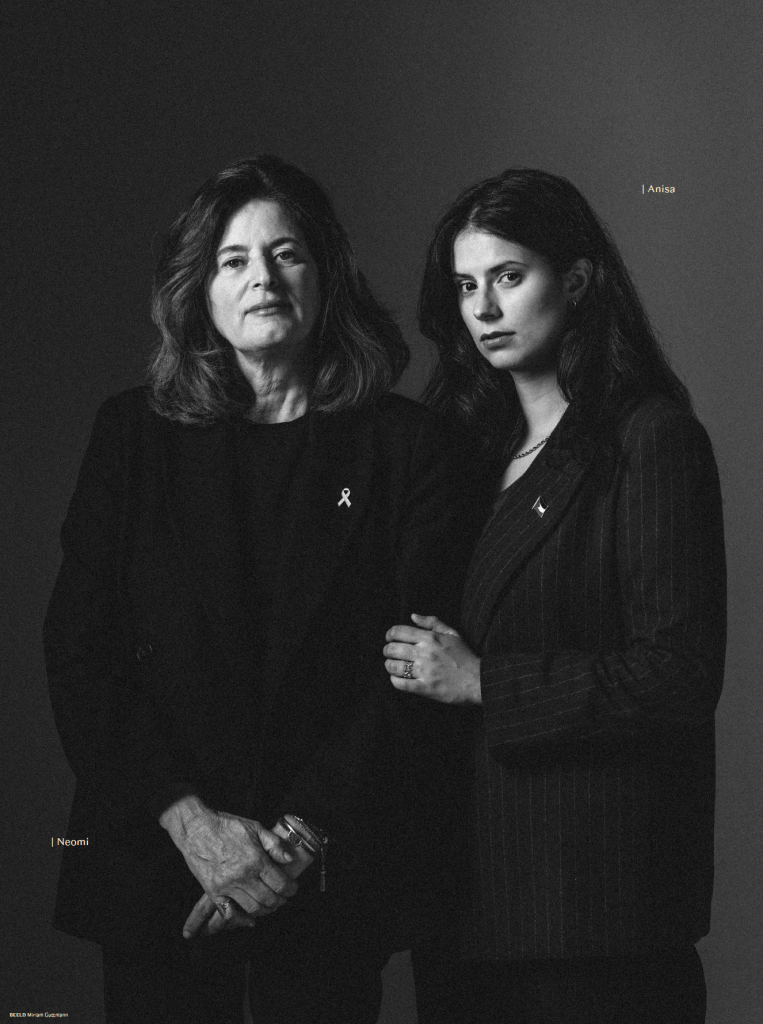

Neomi (62) was born in Israel and has now lived in the Netherlands for 33 years. Anisa is half Dutch and half Palestinian. Her Palestinian father died when she was 7 years old. Anisa (27) grew up in the Netherlands, but her father’s family lives in Gaza.

Neomi: ‘My husband is Dutch and I gave my children a Jewish identity, but they are Amsterdammers. That’s why I sometimes feel lonely in my own family. They don’t feel the sadness the way I do. I grew up in Israel and love the country very much.’

Anisa: ‘I recognise that feeling of loneliness. I grew up with a Dutch mother who doesn’t feel the Palestinian pain the way I feel it. It’s not a grief you carry together.’

Neomi: ‘Everyone goes on with their lives here, while you and I are very much at it.’

Anisa: ‘You wake up with it every morning and go to bed with it every night. There are days when I am incredibly angry, or very sad, there are also days when I feel nothing or days when I can enjoy life again.’

Neomi: ‘I demonstrate a lot. For the release of Israeli hostages by Hamas, but also against Israeli violence in Gaza. Israel was built out of trauma. So many mistakes were made there. My mother, who was in hiding during World War II and is now 90, said to me the other day: ‘You know, when we arrived in Israel, we didn’t realise at all that Palestinians were already living there’.’

‘We should have learned at school about the Nakba (the formation of the state of Israel in which Palestinians were driven out of their homes and murdered, ed.) and compulsory Arabic. I regret how this was done and it created monsters. At the same time, it is where I grew up, I love the land, the culture, the humour and I recognise Israel’s right to exist. That’s why I don’t think the slogan ‘from the river to the sea’ is acceptable, it calls for Israel’s destruction.’

Anisa: ‘I don’t agree with that. That slogan means that Palestinians should be able to live freely. I don’t think the Israelis should leave, but the Palestinians are living under an occupation. This must end, peace alone is not enough. I wear a keffiyeh (black-and-white or red-and-white Arab scarf, also called the Palestinian scarf, ed.) to speak out against this injustice, but sometimes I feel unsafe when I wear it.’

Neomi: ‘I understand that fear, the other day I was in a taxi with my mother and the driver asked where we were from. I didn’t dare say from Israel. It’s bad that you don’t dare to express your identity. At the same time, I wish precisely that symbols and flags were not needed. That we don’t wear keffiyehs and stars of David, but look for equality.’

Anisa: ‘I agree, but as long as Palestinians are dehumanised and oppressed, I feel I have to do this.’

Neomi: ‘I understand that too, your struggle for a minority. I would like everyone to fight for the rights of all people. With all the money being put into war now, you could feed everyone in the world and make it such a beautiful place. I am always an optimist, but I see the future very bleak now.’

Anisa: ‘Still, I keep hope, that’s all you have.’

IN CONVERSATION – and have respect for each other’s perspectives

Imam Shamier (49) and Rabbi Awraham (81) think it is perfectly normal to spread the message of connection together. So they regularly do so in schools.

Awraham: ‘We go to schools together to talk to young people. We show that we are connected. For instance, we also sat together on the Buitenhof programme and we shook hands there. Totally normal. But after that, people were full of praise. The special thing is that it was so special, because it shouldn’t be.’

‘We often seek the caricature of each other. We talk about ‘the’ Muslim or ‘the’ Jew. We then have all kinds of thoughts about that. The moment we meet, we see the facial expression, the glance, we see the humour. We just see the human being.’

Shamier: ‘We are completely divided into two camps. You are either for or you are against and you must have an opinion. If you don’t have one, you are condemned. My belief is that our creator, is also the creator of the other creations, whether Muslims, Jews, Christians or people of any faith. And if you kill one person, you kill the whole society.’

‘Just when things are chafing and difficult, we need each other to grow together. We need to hold on to each other. That is not easy, but you do that by respecting each other’s perspectives. Acknowledge each other’s pain and make it negotiable.’

Awraham: ‘Because we go to schools together, I get the chance to listen. And I get the chance to be listened to. That’s not easy, because there are a lot of statements being made and I know that if I start talking about Hamas, the divisive point will come, that we’ll be on opposite sides. But the fact that Shamier is also there and we are close together makes it possible. What we do is very common and at the same time it is something that happens far too little. Letting our hearts speak.’

‘Every time I come out of a classroom like this, I feel optimism. This is not a lost generation. I see enormous potential, compassion, drive, but we need each other. I see in the Jewish community that the disenfranchisement has continued and something has come along. Anti-Semitism has taken wings. That has gotten worse since the violence in Amsterdam.’

Shamier: ‘I get criticised for the connection I seek with Awraham. I am told to stand up for the Palestinians. But my message remains: get to know each other. That is also written in the Quran. And that is needed now more than ever.’

Awraham: ‘My hope is that all these small moments together become a big moment. That we sit here together and that the Almighty who created us gives us the strength to carry on. I may not ask for it, but our conversation is also a prayer. I feel sad that I cannot let young people inherit a better earth.’

Shamier: ‘Treat the other as you want to be treated yourself. We have so many similarities. And we need to make it clear to young people that it does not matter whether you are Jewish, Muslim, Christian or atheist. It matters who you are as a human being.’

IN CONVERSATION – not to let fear win

Taghreed (54) and Maurice (40) both write about Israel and Palestine. Maurits got involved because his mother is Jewish and she was the only member of her family to survive the Holocaust. Taghreed grew up in Gaza and has now lived in Amsterdam for 13 years.

Taghreed: ‘Keep talking about what is happening in Gaza and keep learning. Don’t be afraid of being accused of anti-Semitism if you speak out against the injustice done to Palestinians. It has nothing to do with religion.’

Maurits: ‘Speaking out is the least you can do. People need to know about the injustice of the Israeli occupation of Palestinian territory and the genocide.’

Taghreed: ‘I keep having flashbacks of the beautiful memories of my neighbourhood, all the beautiful places have now been swept away. My school, my favourite restaurant, my sports club, they are all gone. Our house was shelled but is still standing, everything around it has been completely destroyed. I am most sad about my photo albums, I left them all behind. I was afraid my whole family would die, but some of them managed to flee to Egypt. Since then, I can breathe again and have the strength to keep talking about it.’

Maurits: ‘I feel a great responsibility to speak out against injustice. As a child of the diaspora (dispersal of a people around the world, ed.) with a genocide that my family experienced just one generation ago, I cannot remain silent now that it is the Palestinians who are being massacred. I was always taught that what happened to the Jews can happen to other minorities as well.’

Taghreed: ‘Speaking out, demonstrating against injustice, that’s a great thing. A lot is happening in Amsterdam and I think that’s great to see. But we have to make sure that the right to demonstrate remains protected. And I think education must improve. Conversations should be held in schools. It’s not bad if people see the world differently, but you have to be able to talk to each other about it. Teachers no longer know how to do that.’

Maurits: ‘If those conversations are not had and are not taught in schools what is happening in the world now, it is not only harmful for the students who do not yet have this knowledge. The young people who do know what is happening in Gaza now, because they see the images on social media, for example, or hear about it from their parents, they lose confidence in the education system and thus in important institutions. And that creates more division.’

‘When I used to learn about the Holocaust and Israel in school, it was never about the Palestinians. I do see that awareness is tilting. More people than ever are standing up for the Palestinians. And yet sometimes it makes me despondent. We all live in bubbles, not everyone gets the same information.’

Taghreed: ‘We need to educate critical thinkers in the Netherlands, have the debate at universities. We need to educate a generation and we should be proud that we have the opportunities to have these conversations here. Make it clear that this is not about religion, but about politics. If you are against refugees, be against war too. I think Maurits and I should go together to all the schools in Amsterdam to tell our story.’

Maurits: ‘I think that’s a good idea. We must not let fear win.’

IN CONVERSATION – Not to get stuck in your own anger

Bekend maakt bemind, is the name of the initiative of Amsterdam councillors Itay (30, Volt) and Sheher (37, DENK). For over a year now, they have been calling on anyone who wants to hear: please talk to each other. This exhibition came about because of the motion they submitted to the city council. Itay is Jewish and has family in Israel, Sheher is Muslim and often speaks out for the Palestinians.

Itay: ‘There is little pity or understanding for “the other side”. But then when I ask people if they ever talk to ‘the other side’, the answer is no. So then you can’t understand each other either. People think they have to give up something of their own identity to enter into that conversation. The first question asked is: do you condemn Hamas? Or: do you condemn Netanyahu?’

‘If human rights is your shared value, then it makes sense that I condemn Hamas as well as condemn Netanyahu. If human rights are violated – it doesn’t matter by whom – then I condemn it. When I talk to someone who doesn’t have those shared values, I find it very difficult.’

Sheher: ‘We no longer see each other as people. Anyone who belongs to a minority group in the Netherlands is told to leave the country at the slightest hint. We shouldn’t let ourselves be played off against each other.’

‘Of course there are limits. As far as I am concerned, they always lie with human rights and they apply to everyone. So that is the opposite of: own people first. I don’t need to have a conversation with someone who says women should pay head scarf tax – tax for wearing a headscarf. Then you are talking about my wife and by engaging in a conversation with such a person, I legitimise those views.’

Itay: ‘I used to not need to have a conversation with someone who denies Israel’s right to exist, because then I didn’t think I had shared values. I thought the same about you at the beginning, but now that I know you, I know we have a lot of them. If you never start the conversation, you’re never going to discover those commonalities. At the same time, what you say is true, you do have to draw a line somewhere. Where exactly that is is tricky.’

Sheher: ‘The most basic thing is human rights. You don’t ask for that much. I think you should always keep the door open for the other person, but in some cases the other person has to come in.’

Itay: ‘Yes, but yes, what if you are both like that in it? Then no one will ever come in. We have also both stepped forward.’

Sheher: ‘Yes, but I don’t go to someone’s house to be a second-class citizen there. You can have different views, but you have to accept Muslims. Then I go in.’

Itay: ‘Sometimes I also think never mind that whole connection thing. It’s often much easier to stay in your own anger. It takes a lot of energy to take that step forward, to always put yourself in the other person’s shoes. I am not giving up my identity by taking that step, but many people around you think I am. I am told that my actions create anti-Semitism in the Netherlands.’

Sheher: ‘I too get criticism, but then I explain that I see Amsterdam as a mosaic, where everyone can find their place and be themselves. Such a mosaic only works if you set the framework and leave room for the other. You can only be free if the other person is also free.’

IN CONVERSATION – to counter harshness

Journalist Salwa (32) and filmmaker and photographer Miriam (30) met during so-called ‘connection dinners’ that Miriam organises with her sister to bring Amsterdam Jews and Palestinians together. Together they worked on this exhibition IN GESPREK. Salwa guided and wrote out the conversations, Miriam made the duo portraits. Miriam comes from an Amsterdam Jewish family, Salwa has a Palestinian father.

Miriam: ‘I knew immediately during our meeting that I wanted to do a project with you. We found each other in the common pain we felt, the overwhelming sadness and powerlessness. That’s why I started those dinners. I wanted to counterbalance the harshness, the polarisation. The violence there, it’s too big. I try to focus on what I can do here.’

‘In my parents’ house there is a card by the Jewish writer Primo Levi that says “it happened and therefore it can happen again”. Never again for me always meant: never again for everyone. For me, standing up for Palestinians and their struggle is not in contradiction with my being Jewish. On the contrary, it is an extension of it.’

‘Judaism and Israel are constantly conflated. Criticism of the state of Israel is not the same as anti-Semitism. This mistake contributes to Israel continuing to commit war crimes undisturbed. By dismissing criticism of Israel as anti-Semitism, you hollow out the concept, and that is dangerous. Especially as we see unadulterated anti-Semitism on the rise.’

Salwa: ‘My family is from Gaza and the past year has been horrible. My father was only able to flee after six months of bombing and he is one of the few who managed to do so. I really didn’t always feel the need to ‘connect’ during this year. I didn’t see the point at all, I was only concerned with the grief for my family and all the children in Gaza without food, without limbs, without parents. But the importance of doing it is greater. And you seemed to understand my grief better than many other people a bit further away. Precisely because you have family in Israel.’

Miriam: ‘I recognise that. For many people here, life goes on as usual. For us, it often stands still.’

Salwa: ‘I also feel more Palestinian now than ever. During this project, I learnt a lot from all those portrayed. I loved seeing how willing everyone was to talk to each other. At the same time, of course, connecting doesn’t just happen. You often need something from the other person. I wouldn’t be doing this with you either if you didn’t condemn the genocide in Gaza.’

Miriam: ‘I understand that and that’s why I think it’s also important to say that we’re not trying to smooth anything over with this project. We are not denying the genocide or the power differentials. With this project, we are trying to give a face to people here in Amsterdam who will not let themselves be played off against each other.’

Salwa: ‘I am convinced that this is needed now more than ever. That we need to set an example, to counter the hardening and hatred. There are more of us.’

IN CONVERSATION – because nothing is self-evident

Achraf (27) was born and raised in Amsterdam with Moroccan roots. Micha (72) was born in Israel and has now lived in the Netherlands for 46 years.

Micha: ‘In 1978, I walked with a large backpack and a sleeping bag from central station towards Dam Square. I was on holiday and not even ten minutes in Amsterdam when I said to a friend: this is where I feel at home. I never left. I have now lived in Amsterdam for 46 years. I still have family and friends in Israel, but Amsterdam is my home.’

‘I have always really appreciated the fact that we live in so much freedom here. That’s why I’m also so terrified that that will change. It’s very fragile. It can break down in one fell swoop. The situation in the Middle East there, that is very bad and sad. But I also think it’s bad when Islamophobia and anti-Semitism increases here, in the Netherlands, because of what is happening there. When the Maccabi supporters were in Amsterdam, we saw how that can go wrong.’

Achraf: ‘I firmly believe that it is not about a problem between Jews and Muslims. Somehow, that is how the outside world sees it. I would like to counter that image by participating in this exhibition.’

Micha: ‘We should do everything we can to make sure it doesn’t trickle down here. We must cherish the freedom we have here in the Netherlands.’

Achraf: ‘I totally agree that we should do everything we can to prevent it from creeping in here. We should cherish the freedom we have here in the Netherlands.’

Achraf: ‘I completely agree that we should do everything we can to prevent it from creeping in here. But we must also remain realistic. I know many people, including myself, who can no longer identify with Dutch identity because of Dutch involvement in the Middle East situation. If we want to ensure that we continue to get along well here, we must also take a critical look at our own government.’

‘Anyway, I feel much less at home since the victory of the current government. I am also considering leaving. To Morocco or another country where I don’t have this kind of nonsense on my mind, to put it in Amsterdam fashion.’

Micha: ‘As citizens, we are often the victims of flawed politics. Most people just want to live nicely together. I don’t want to argue with you. I have always had Arab friends. I think, precisely with all citizens, regardless of origin, we need to become stronger together, hand in hand, and speak out against violence.’

Achraf: ‘Our Amsterdam identity must transcend a lot. We must keep looking for nuance and not just speak to our own parish. I think it’s important to remain a connector, even when things come to a boiling point in the city, like the time with the Maccabi supporters.’