Intersex 1 in 90

While we are becoming more accustomed to people who don’t fit into boxes, a large group of Dutch people still live with a secret. They are intersex: born with a body that is different from what we consider as male or female. They have characteristics of both. Sometimes it becomes evident at birth that a child is intersex, as their physical characteristics may not clearly indicate whether they are a boy or a girl. More often, there may be no visible external signs.The variation can be internal and can become apparent later on. For example, when a teenage girl does not start her period.

Intersex 1 in 90 in an initiative by journalist Lara Aerts, photographer Ernst Coppejans and the Open mind foundation and refers to the I in LGBTQIA+.

Secret

1 in 90 people is born with an intersex variation, also known as a Difference of Sex Development (DSD). The official policy regarding intersex until some time ago has been to keep it a secret and make the body more male or female through medical procedures. Slowly but surely, there is more openness in society about intersex now. The medical practice is changing too, although recent research shows that genital surgery is still being performed on children under the age of 12 in the Netherlands, even if it is not medically necessary and the children cannot have a say in the decision.

Taboo on biological sex diversity

Biological sex diversity maintains a taboo in our society. This portrait series aims to change that. 21 intersex people come forward with their experiences: what is it like to live in a world that is divided into men and women while you have a body that does not fit into either of those boxes? If this exhibition proves anything, it is that everyone experiences it differently. Yet, there are also parallels among those portrayed. Living with a secret, for example, weighs heavily. Just like the medical procedures people could not have a say in. Almost every person relates to the biology lessons in school, intersex is – to this day! – being denied. Another common denominator is the relief when the secret has been revealed and the responses are generally positive.

Inclusive society

There is one thing that all those portrayed agree upon: there needs to be more knowledge and societal awareness about intersex and the existence of biological sex diversity. Biological sex is a spectrum with infinitely many variations, much more than just male and female. For intersex people, it is only truly safe to come out when society knows they exist and that it is perfectly natural and normal to be intersex.

On tour

Starting from May 2023 onwards, this multimedia exhibition will travel to various municipalities in the Netherlands. In addition to the exhibition, we will organize an impact program in collaboration with local partners, such as guided tours, panel discussions, and other knowledge-sharing events where social partners, municipalities, governments, healthcare and educational institutions, and advocacy organizations can learn and share information with the public about intersex. The project also includes a magazine, podcast, and a short documentary. For more information; Tess@stichtingopenmind.nl

Portraits

Leigh (37)

Diversity officer

It didn’t have to be a secret

Kitty Queerboot

‘How cool!’, people exclaimed when I wore a T-shirt with the text ‘I am Intersex’ during a Canal Pride event in Utrecht in 2017. Even outside the LGBTQIA+ bubble, everyone responded positively. It was a huge relief. Within that same year, Dutch actor and artist Raven van Dorst released the first episode of their series Geslacht! which is about how biological sex plays a role in Dutch society. Ever since they came out as intersex, there has been a lot more attention for being intersex. It was definitely a turning point.

Job

My coming out got me a job at NNID (a Dutch organisation for biological sex diversity). My job was to support intersex people from all over the world reporting complaints about human rights violations to the United Nations (UN). I loved this job. Based on recommendations by the UN, legislation has been enacted in multiple countries to improve the protection of intersex people’s rights.

Secret

When I was seventeen, I found out that I was intersex. I underwent a very painful and, at that time, unnecessary surgery. I wasn’t allowed to talk about it, because nobody would want to have anything to do with me. So, I kept the secret to myself instead of telling the people I loved. They, however, always told me personal things, but I could never do that. This created a certain distance between me and them, and I also struggled with it in relationships. It took a very long time to confide in people I loved.

The United Nations

The United Nations claim that medically unnecessary surgeries or hormone treatments on young children without their consent is a serious violation of human rights. This statement was already made back in 2015. In 2018, the UN urged the Netherlands to put an end to these surgeries and treatments, which the UN had to repeat in 2022. They have a very clear point of view: intersex children should have the right to decide over their own bodies. Parents are responsible for the care of their child, which also includes medical care. However, parents should not decide everything in their child’s life.

Parent’s role

If a child is born intersex, their parents often make decisions based on the limited amount of information they have. Parents completely depend on just one or more doctors, and on top of that, they are sometimes still in shock after finding out their child is intersex. I truly believe that for some children, parents will make the right decision when it comes to choosing their child’s gender. However, it’s just impossible to predict in advance whether the child will be happy with that decision or not. In some cases, the right gender was chosen, but later in that child’s life, it can be unhappy about not having had a say in that decision.

Activism

I have always had a strong moral character. I think it’s important to act with integrity. However, speaking my mind hasn’t always been easy since I couldn’t express my true self. When you’re keeping everything about being intersex a secret, this is what happens. Eight years ago, I became vegan because I didn’t want to contribute to the suffering of innocent animals. Other than that, I now also want to help reduce human suffering. After I could finally be my true self, I also dared to speak my mind as an activist. My activism helped improve my coping strategies, since I was now able to stand up for my own rights. One of my jobs is also to make the world a better and happier place, which is a slow and difficult process, but that doesn’t stop me from dedicating myself to doing so. It’s worth all the time and effort spent.

Growing intersex visibility

In these past five years, intersex has become more visible than ever. During the Canal Pride in 2017, where it all started for me, I believe I was the only visible intersex person. However, when I participated again during the Canal Pride in 2022, to my surprise, I saw some intersex flags on the quay. And the boat I was on was packed with intersex people. Nowadays there are theatre plays and documentaries about being intersex. It’s obvious that the visibility is growing and that our human rights are being taken more seriously. The majority of the votes in the Dutch parliament are in favour of a ban on unnecessary surgical procedures on young intersex children, which I never could have imagined five years ago. So much has happened in such a short period of time.

Marleen (31)

Theatre producer

It felt like I had a monster inside of me

Biology class

When I was five years old, they discovered that I have both X and Y chromosomes, and also that my body doesn’t respond to testosterone. Bit by bit my parents informed me about it and I remember them telling me that I’d have to take certain pills to grow breasts in the future. They also made it clear not to talk about it, except with DSD Nederland, a Dutch peer support group. It was nice spending time with others who’ve got the same condition, nonetheless, everyone was still terrified that our secret would be revealed. Everywhere I went it became clear that my condition shouldn’t even exist in the first place. That was confirmed in biology class, during which I learned that women have XX chromosomes and men have XY chromosomes. I then asked if I as a girl could have XY chromosomes. My teacher answered that it wasn’t possible.

Monster

The outside world saw me as an open and cheerful person, but on the inside I felt rather lonely. I thought to myself: if others would ever find out who I really am, who’d even want to be with me then? My secret turned into something like a monster that seemed to take over my body and eventually my identity. I felt like some sort of freak then. I didn’t confide in anyone until I was in my twenties, but even then I told them not to say anything about it to anyone else. When I was 22, I confessed everything to a lifelong friend of mine, and she kept on pushing me to seek help, because I was totally confused.

Theatre

In therapy I learnt that the Androgen insensitivity syndrome (AIS, the medical term to describe my intersex variation) was nothing but one of my many characteristics. Step by step I learnt to share my story with others and I also started making theatre productions regarding the subject. X Y I is a rather personal play in which there’s only my character, and X Y WE is a group play with other intersex people. As I put my story into words and spread it across the world, the monster got smaller and smaller, until it became so little, it fitted in the palm of my hand. Even now, I can’t help but to think: am I actually going to share my story? Am I really going to do it? But now that the little monster doesn’t affect me as much, I’m capable to approach the matter and all that comes with it.

Positive comments

I blamed my parents for a long time, because of their strong advice not to talk about it. But they explained to me that there were three doctors in the hospital who emphasised that it would be best to keep everything a secret. I understand why people used to think that way in the fifties or sixties. The idea was to protect kids from society. But the advice to keep it quiet persisted long into the 21st century, even when research showed it to be harmful. I have never had to deal with negative comments after I came out. Even though I live in a small village. Most people simply responded with: ‘Oh. Well, I couldn’t be bothered with your chromosomes.’ Turns out I have been lonely for all those years for no reason at all. I am still furious about that.

Who am I?

I have already shared my story many times publicly. For example, I opened up about me being intersex in the Dutch tv show Spuiten en Slikken (Dutch for Shoot and Swallow) and I mentioned it on the Dutch live tv show with Humberto Tan, a famous Dutch tv host. Addressing the topic helped me process my story. But my story doesn’t stop there, instead, it’s an ongoing process. I now have reached a point where I wonder: who am I without my secret? I remember the patient association always emphasised that we’re real, normal women. At first, I always used to stress this statement as well: I presented myself as a real and normal girl. But now, I realise that I don’t exactly know who I am, not even when it comes to being a man or a woman. People often ask me whether I feel like a woman. I always respond by asking the same question: do you truly feel like a man or woman? Oftentimes, people aren’t sure how to respond. Because what does feeling like a man or a woman actually mean? Is it really necessary to have a clear answer to that?

Identity

It wasn’t until five years ago that I first heard the word intersex. For me, the word refers to a variation in biological sex rather than a condition. I started to realise that intersex is more than something I just happen to have, because it’s now such an important part of my identity. And by that I don’t just mean the biological aspects, but also my duty to inform and educate today’s society. All of this has had a huge impact on myself as a person, so now I tend to say that I am indeed an intersex person instead of having an intersex condition.

Ella (65)

Software developer

Beyond the shame

Lump

When I was born, the doctor thought I was a boy. I didn’t have testicles, and I had some sort of lump instead of a willie. I read girls’ books, just like my sisters did. We built LEGO houses that we used for playing with our dolls. We had a warm bond, we still do. But I felt guilty towards my parents. I felt they were disappointed, all because of me. Especially my father. He tried to turn me into a boy and sent me outside when I was playing with dolls. When I was about four years old, my mother told me I’d never get married. She told me I could never talk about what I had with anybody, let alone show it. Apparently I should be ashamed of the thing between my legs.

Societal changes

The feeling of not being good enough is profound and will never go away, even though I have learned to accept myself. I notice it when talking with friends. When there’s a difference of opinion, I instinctively think I did something wrong. Only recently I started standing up for myself more. That is because society is slowly changing. There’s more attention for diversity of all kinds: colour, gender, biological sex. We as intersex people fight for our human rights. That makes me feel good.

Showering with the boys

I remember showering in secondary school for the first time. I had never seen a penis before and obviously I immediately noticed how different mine was. Then I knew: I’m not a boy. And: people can never, ever see me naked. The remainder of my puberty was mainly about hiding myself. I was always the first or the last one to sneak into the shower, turn myself away from the others and wrap myself in a towel, or whatever. I never got caught. But it did burn me out.

Burnout

When I was 17, I broke down completely during a youth camp. My parents thought I was homesick. In hindsight, I do think that’s odd. Imagine having a son who doesn’t have a notable penis, who plays with girl toys his entire childhood, doesn’t go through puberty and looks like a 12-year-old girl at the age of 17. You would have him checked out, wouldn’t you? My parents didn’t. We didn’t talk about it. They didn’t ask me how I felt about it. They just left me to it.

I wanted to be normal

My sister got me help at the right time and I ended up at the doctors. After an appointment with a psychologist, I was advised to start taking male hormones. This was probably because I was registered as a boy, I had a boy’s name and I didn’t clearly state that I wanted to be a girl. Honestly: turning into a man was not at all what I wanted. My lack of sex hormones meant that I was still a child, mentally. A child that was pretty content with its imperfect body, but that wanted to be normal above all. I wanted to belong, that was all.

Male hormones

This male hormone therapy was a grave mistake. I changed a lot: I grew tremendously and got a low-pitched voice. It’s all-decisive and irreversible. I quit after half a year, then I spent years living in some sort of no man’s land. It took me until the age of 45 until I stopped thinking about it every single day. Eventually, through surgery and female hormones, I got a female body.

Forgiveness

I don’t blame my parents. It was difficult back then. They didn’t get any support from the hospital. On her deathbed, my mother told one of my younger sisters: ’I’m glad Ella turned out fine’. I think it’s tragic that she’d been remorseful her entire life, but didn’t share any of her feelings with me. She could have said something like: ‘My dear, I’m so glad you’ve made it’. Because in the end, I did make it.

I am normal

I don’t pity myself. I used to do so. I blamed intersex for the misery in my life. But that wasn’t right. Every person goes through bad circumstances in their life. Through the years, I learned that I’m in fact pretty normal. Even though my past was atypical, I have the same needs as everyone else. That’s the most important thing people should know about me.

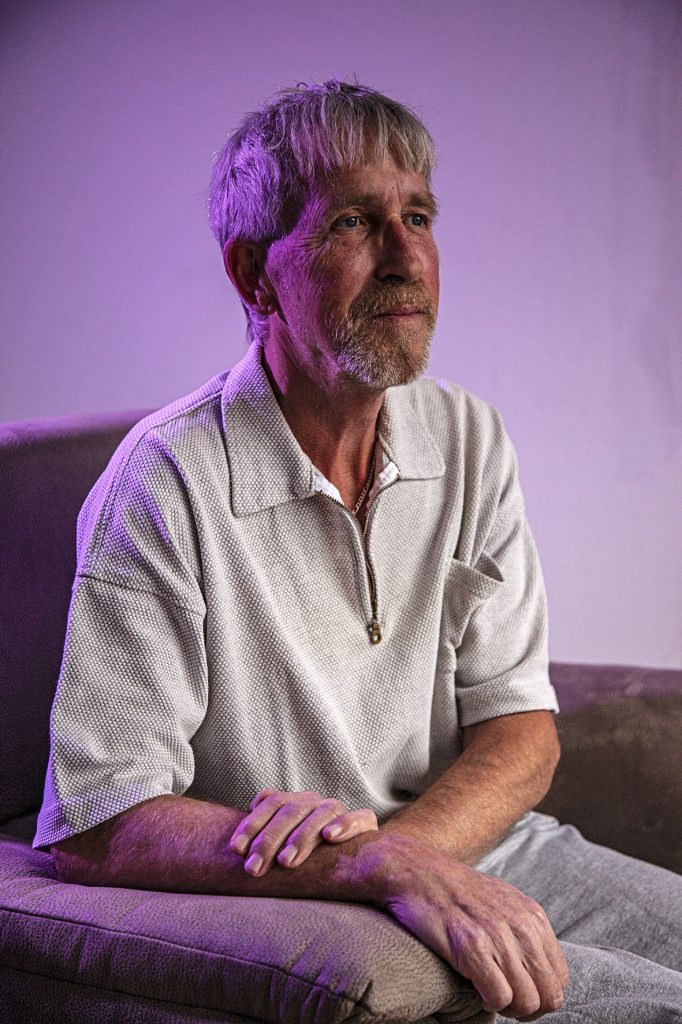

Geert (62)

Operations manager

Aged sixty I discovered I am intersex

Hiding

As a child, my life was all about hiding my body. Whether I was changing my clothes for P.E., for football practice, or at the pool. Because of my micropenis, I wasn’t able to pee while standing up, so I had to plan everything I did beforehand. I wanted to avoid ending up somewhere in a latrine with friends, or having to pee on the side of the road. Even during summer, I used to wear loose-fitted blouses and sweaters to hide my breasts. The constant lying, beating around the bush, and the fear that people would discover that I wasn’t a ‘real’ man completely destroyed my self-image. And it’s still taking its toll on me. All I know is that my name is Geert and I’m sitting on this chair right now. But honestly, I don’t have any clue who I truly am.

Freemartins

Unlike me, my twin brother is considered ‘normal. So I always knew I was different from the rest. I grew up on a farm where animals were born who couldn’t be specifically labelled as male or female. Hence, we called them freemartins. They couldn’t produce milk or reproduce, so they were basically worthless. I knew I was like them. After I had genital surgery, my friends at school asked me: ‘how’s your leg?’ Apparently my parents told my teacher that I had knee surgery. It made me realise that I had to keep my mouth shut. No matter how young you are, you notice that men with small penesis are laughed at. You know it’s something to be ashamed of and it’s something you’ll be humiliated for. Not just by men, but also by women.

Multiple surgeries

When I was around ten years old, my urinary channel was moved by surgery, but it went wrong. I was in a lot of pain, and I had fistulas everywhere from which my urine leaked. I was too afraid to tell my parents, since my older brother had just died in an accident, so I figured they already had enough to deal with. It wasn’t until I turned 17 that I decided to confide in my sister. We went back to the hospital, and countless recovery surgeries followed. Nonetheless, it never really got any better, as the part between my legs is completely mutilated. During my childhood, we never talked about what was going on. Even when my breasts started to grow, my parents and the doctors didn’t say a word. I felt like a failed human being, and incredibly lonely. I remember standing in front of my brother’s grave, thinking to myself: I wish I was in your place. But I also knew I couldn’t just end my life since my parents had already lost a child.

Relationships

Being in a relationship is very important to me. It makes me feel like I matter. I’ve been married for thirty years. My ex-partner has two kids and I’m like a dad to them. I got divorced at the age of 60 due to a lot of things, except for me being intersex. After the divorce, I decided to take a step back and take a closer look at myself as a person. I was desperate to learn more about myself. And who was Geert anyway?

PAIS

Two years ago, I got access to my medical records, and I found out that I have PAIS (Partial androgen insensitivity syndrome). This means that I am partly insensitive to testosterone and that my body has developed in a way that’s partially male and partially female. It turns out my doctors knew about this for a very long time, but they never said anything to me. They never even mentioned the word intersex. I only discovered PAIS when I googled it. During my search, I came across someone called Marleen Hendrickx, who’s also intersex. She was looking for intersex people to join her play X Y WE, so she came to see me. For the first time ever, I felt like someone finally saw who I truly was, someone who actually understood me! I went on a theatre tour with her and other intersex people. At the age of 60, I decided to step out of the shadows and tell my story to the world.

Supporting others

Even today, life’s still very difficult for boys and men with small penises. This actually applies to everyone with a biological sex that’s different from the ones you see in biology textbooks. When searching the internet, you’ll find nothing about men with PAIS. That’s exactly why I’ve been sharing my story in the media for the past two years. Now, other intersex people contact me just like I contacted Marleen back then. Parents of children with PAIS and adults suffering from this condition approach me when they read something about me or when they see or hear me talk in the media. I hope I’ll be able to support them, one way or another. I’d like to give them the recognition I never had. Because what I went through as a child, is something I wouldn’t wish on my worst enemy.

Leonne (61)

I have an X in my passport

Civil registration

When my father went to register my birth at the municipality, the registrar asked him whether I was a boy or a girl. ‘We don’t know’, my dad said. But he was obliged to choose and thought I would have more successful career opportunities being a man. Besides, he already had two daughters.

Happy youth

My youth was the best time of my life. I grew up in a small village in Limburg. My parents loved me unconditionally and they accepted me for who I was. I was the third kid. It was a home birth, and there wasn’t a doctor involved. My parents both grew up on a farm and often, freemartins were born. Those animals were neither male nor female, they were both. Thus, my parents weren’t quite as surprised when they had me.

God doesn’t make mistakes

According to the medical protocol back then, children like me should have surgery to become either a boy or a girl. As for myself, I never had that surgery. My father knew the bishop personally and said: ‘Everything created by God is good, because God doesn’t make mistakes.’ In our family, little emphasis was placed on gender or biological sex. My father just loved buying us all kinds of toys, and he didn’t care whether those were made for boys or girls.

Angel

I didn’t know I was different until I started going to school around the age of six. Kids at school asked me: ‘So, what are you? Are you a boy or a girl?’ When I asked my mom about it, she told me: ‘You’re an angel.’ And with that answer I went back to school. My father made me do many sports, and I became really strong. So, whenever kids were bothering me, I would beat them up. Hence, they considered me a rather annoying angel, nonetheless I also gained their respect. This was how I survived at school.

Decent lover

In secondary school, I began to behave more and more manly. My parents encouraged that behaviour as well. I was playing water polo which made my muscles grow immensely. Because I was a gentle person, my father recommended that I become a nurse. During the nursing course, people accepted me for who I was. I even had many girlfriends I would also sleep with. They didn’t mind the fact that I had small genitals. I knew how to please and satisfy my girlfriends in other ways and I was well-known for being really good at it.

Family

I really wanted to have a family of my own. Hence, I got married and at 23 years of age I became the father of a boy. I was truly happy and proud, but along the way I discovered I preferred being a mom over being a dad. After this realisation, I went to India to find my true identity. There, I talked to gurus and after a while I discovered that I wanted to live as a woman. When I came back to the Netherlands, I started my transitioning period. At the time, being sterilised was mandatory, which was such a dumb rule. The state has actually recently apologised to trans people for this. After completing my transition, it wasn’t possible for me to have more biological kids.

Court case

I had lived as a woman for seventeen years, but over time it turned out that being a woman didn’t make me happy either. In society we know only men and women, and this had forced me to choose. Along the way, I discovered my gender was right in the middle. Legally this was not an option at that time. So, I started a court case to get an X – sex unknown – in my passport and on my birth certificate. In 2017, the judge decided to accept my demand. He too was convinced it was about time to legally acknowledge biological sex diversity. I happened to be the first person in the Netherlands and it got worldwide attention.

Grandy

My son now has two kids of his own. He still sees me as his dad, but after the birth of his first child, he asked how I would like to be called: grandpa or granny. It became a mix of the two titles: ‘grandy’. I really loved that my grandkids use this word. As a result of society’s pressure, I was always forced to choose between being a man or a woman. But since I’m both, I simply can’t just choose between the two of them. I have to cherish both sides. And I’m able to do this by being a grandy to my grandkids.

Mila (3)

Mother Janis: No problem Mila being different

Informing the teacher

Tanguy (27, entrepreneur): Mila just turned three and soon she’ll go to school. Since she looks like a girl from the outside, we first tried keeping her being intersex a secret from her teacher for as long as possible. Nevertheless, we eventually informed the school about the situation. We are aware that intersex is very unknown and that most people still think the world consists of only men and women. We wanted to prevent any of this misinformation being passed on during class which could make Mila think like: ‘huh, what about me?’ The teacher responded very positively when we discussed the topic. She promised to inform other teachers about it and she said she’d take it into account during class.

Surgery

Janis (26, entrepreneur): We always discuss the situation when Mila is around, so she’ll grow up knowing that she is an intersex person. When she reaches puberty, she has to take hormone pills for her body to develop maturely. The tissue that normally develops into ovaries or testicles and which stimulates the production of sex hormones during puberty, was surgically removed from her body. According to the doctors, not removing the tissue could cause cancer. Shortly before the surgery, they told us we could make the decision ourselves. But they also mentioned that it was important to remove the glands, and they told us that most parents would do the same.

Tanguy: I wasn’t sure about the surgery on Mila. On the other hand, doctors were talking about a 30% or 50% chance of cancer development. The moment Janis heard about that, she got really scared and wanted them to perform surgery on Mila sooner rather than later. We got carried away and didn’t think it through properly, because we ourselves didn’t know what was best in this situation.

Puberty

Janis: It bothers me that she will have to take medication in the future, that she will start taking hormones. Nowadays, I wonder whether we should’ve let them perform surgery on Mila. I learned that some intersex people keep their glands, which leads to their body developing naturally during puberty.

Tanguy: I don’t worry about that anymore. The surgery has been done and we can’t turn back time. So for now, I just want to enjoy this stress-free time while she’s still young.

Noninvasive prenatal testing (NIPT)

Janis: All I want to do is prepare myself and read about it as much as I can. So that I don’t have to question myself later on whether I should or shouldn’t have done something differently. This takes me back to all of the examinations that took place during my pregnancy, like, for example, noninvasive prenatal testing (NIPT). The test can identify birth defects and also the biological sex of a baby. According to NIPT Mila was a boy. But the ultrasound clearly showed us that Mila was a girl. To me, it didn’t matter much whether Mila was going to be a boy or a girl. But after five months of pregnancy, an amniocentesis was recommended and then it turned out that the baby had male chromosomes, a vagina and a uterus. Still, I didn’t worry about any of it. Doctors told us that, once Mila was born, they would perform a brain scan, take her blood and that they would perform surgery on her. To me, it felt like she had an illness that had to be treated, and that bothered me. I mean, she was healthy, right?

Abortion

Janis: When they announced during pregnancy that Mila was intersex, they basically explained to us that she would be born female, but that she would barely have any breast development later on in her life. I’ve got small breasts myself, so I thought: so what? Subsequently, they told us we could still abort her. I was truly appalled. Abort our baby just because it’s hard to say whether the baby is going to be a boy or a girl? I thought: there isn’t anything wrong with her, so what was the problem?

Tanguy: I feel like doctors are obliged to give the option to abort. Perhaps some people don’t prefer having a kid that is a bit different. But there are already so many people on this planet who are intersex, and who are just living their lives like any other person, so what’s all the fuss about?

Janis: Aborting a perfectly healthy child just because of its chromosomes is beyond me. Abortion was never an option. To us, Mila is who she is, and that’s that. Being a bit different is not an obstacle in any way.

Bart (47)

Attendant in the disabled care sector

I was simply allowed to join ballet classes

Family

My mother has a sister who’s intersex. When my aunt was a child, it wasn’t clear whether she was a boy or a girl. In my case, there’s no doubt about my biological sex, even though I look different from other men. Because my mother witnessed how my aunt suffered, she dealt with me in an open and light-hearted way.

Ballet

As a child, people knew me as a boy who liked to play with dolls and do arts and crafts. For Christmas, I got a bed for my doll. My grandpa made it for me. My mother always told me: ’Just be yourself.’ When my brothers started playing football, my mother suggested that ballet might be my thing. She was right: I did classical ballet until the age of 12.

Rejected by my father

My father dealt with it differently. A boy doing ballet? That wasn’t his cup of tea. My parents were divorced, but he clearly disapproved of me. In his opinion, I had to act ‘normal’. Otherwise people would talk. His attitude did more harm than being different.

Crazy about kids

When I was a kid, I didn’t know the word intersex. People didn’t use that word. I did go to the hospital for checkups quite often and when I was 10 years old, a doctor told me I wouldn’t be able to have children. At the time, I was always around small children. I realised pretty well what infertility meant for me. I had to cry and I still remember my mother saying: ‘There are other ways to have children.’ I ended up not having children anyway and I’m fine with that.

(Not) a girl

A while ago, I saw a video of myself when I was 11 years old, doing tricks with a friend. Afterwards, I called my mother, crying, and told her: ‘I was a girl all along’. This brought up a childhood memory of a talk about hormones in the hospital. The doctor wanted to talk to my mother first, separately. It felt like three hours. This made me scared. What if something was terribly wrong? I was bawling my eyes out. When they returned I was asked if I would prefer to be a girl. My ‘no’ was very convincing. No way! Imagine what my father would think! I’m still sad about not being able to be myself back then. Anyway, I feel fine with my body now. I don’t really care about what I am. As a man, you can do things that are stereotypically feminine, and vice versa.

Puberty

During puberty, I was occupied with finding out who or what I was. I suddenly realised I was vulnerable to exclusion, because I didn’t live up to other people’s standards. I liked swimming and doing sports, but I hated changing clothes in the dressing room. So I came up with many excuses to skip sports: forgot my bag, missed the bus. Nowadays when I go swimming, I still wonder if people notice. That will never go away.

Taboo

In our society, there’s a taboo on having a small penis. You hear insults and jokes about it on TV, radio and online. These comments hurt the people they are about. However, I do make those jokes myself as well. Like at work. I’ll say: ‘Well, who am I? My opinion doesn’t matter, my penis is too small.’ Self-mockery gets you pretty far. Meanwhile, the insecurity doesn’t go away. It has spread all through my being, my body, everything I am. It takes power over you.

Done with it

How can I appear to be so strong and happy? Hah! These are sides of me as well. In the last few years, they’ve come to the surface. Around the age of 40, I was done with it. I got rid of all the negative opinions I had about myself. I simply refused to believe them anymore. No, I’m not a loser. No, I’m not a chicken. No, I’m not a… you name it. No! My mindset completely switched. I went to therapy. I’m doing very well now.

Martha (2,5)

Mother Nele: I balance between openness and privacy

The endless maze of medical examinations

Nele (34, psychologist): During my pregnancy, there were doubts whether Martha was a boy or a girl. It didn’t really matter to us, but the gynaecologist seemed worried. After inspecting my abdomen for a long time, he called his wife who is a doctor as well, and started flipping through some books. This made me think that there was definitely something out of the ordinary going on. From that moment on, the endless maze of medical examinations began. We learnt that Martha is intersex and infertile. We had never heard of intersex before. Our gynaecologist was mostly talking about all the potential problems. He said: ‘In her puberty it may become a heavy psychological burden for her’. He definitely wasn’t telling us a neutral story about being male, female or intersex. He also didn’t tell us that people can perfectly live with it and that it’s not an illness or a disease.

Black and white

Our gynaecologist also mentioned the word ‘abortion’, which led us into a difficult time. My partner Jakob and I had different points of view about abortion and we were both processing the news differently. I did consider abortion because I felt guilty towards my child: she would never be able to experience being pregnant. But the genetic research to determine Martha’s exact condition took a long time, and week after week, it became clearer how much I wanted this little child. Jakob and I had many conversations and tried to meet each other halfway, but regardless, the decision was black and white: keeping the child or opting for an abortion. At some point Jakob said: ’I am asking a lot more from you to not let this child be born than to become a father to this child’. Him saying this lifted a huge weight off my shoulders. From that moment on, I started looking forward to having my child.

Experts

When the last test results came through, abortion wasn’t even an option anymore, since I was already 26 weeks pregnant. I look back at a stressful time that could have been avoided if we were informed correctly from the start. By now, Jakob and I have become experts on anything that has to do with intersex, gender and diversity. The information we found on the internet has reassured us greatly. We also learnt that many women like Martha seem to be very happy women with a normal life, relationships and nice jobs. I just thought: what’s actually the problem?

Other parents’ stories

What I missed back then, and actually still miss, is hearing stories from other parents with an intersex child. Those parents are hard to find. I often wonder how they are dealing with it, but there’s something keeping me from contacting them. The thought of hearing other parents’ stories kind of frightens me. I have found a way to cope with everything, and it seems to be okay for now. But what if that will change when I hear the stories of other parents?

One day..

Look, she’s still a toddler and she’s always happy, but I’m well aware that it won’t always be like this. One day, I will have to tell her that she will never be able to have biological children, which scares me. I write down my thoughts and emotions in a journal I have been keeping. This helps me to collect my thoughts and figure things out. For instance, one important realisation I would like to share with other parents is that there are various emotions involved, such as fear, guilt, sadness and grief. Those emotions have absolutely nothing to do with the love you feel for your child and they can perfectly coexist.

Openness about LGBTQIA+

I am happy with the evolution that LGBTQIA+ is going through, and the openness with which it is now being discussed in many places. This will positively affect our child, but for now we still choose to not inform the school Martha attends. I feel very strongly that I have to protect her privacy, and that’s also why we’d like to wait until she can tell us herself what to share and what not to share with others. This is our approach. So for now, we’ve decided to take on a protective role. You always have to look for a balance. It shouldn’t necessarily be a secret but we still have to protect her privacy.

Wen Long (9)

The whole world needs to know about intersex

I’ve known that I’m an intersex person my entire life. To me, this means that I’m a boy and a girl at the same time. It’s normal to me, I’m just like this. Many children like me have surgery when they’re little, so they become either a boy or a girl. This didn’t happen to me, my parents want me to choose myself. Maybe I don’t want to choose at all and just stay the way I am. I feel a bit more like a girl than a boy, about 1 percent. Some people don’t believe me when I say I’m both a boy and a girl at the same time. My teacher said I couldn’t give a presentation about intersex people. She thought it wasn’t an appropriate topic for children. This, while the aim of these kinds of presentations is all about explaining and talking about certain topics. I participated in a documentary, Girlsboysmix (Meisjesjongensmix). And I was on Jeugdjournaal, a Dutch news programme for children. I want everyone in the world to know what intersex means. I want it to be as normal as, for example, being gay or lesbian. Then the topic is well known, I will never have to explain it ever again.

The project

Intersex – 1 in 90 is an initiative of journalist Lara Aerts, photographer Ernst Coppejans, and the Open mind foundation. The project has been made possible with the support of the Prins Bernhard Cultuurfonds – VSBfonds – Amsterdams Fonds voor de Kunst – BNG Cultuurfonds – municipality of Alkmaar – municipality of Tilburg – municipality of Eindhoven – municipality of Nijmegen – municipality of Rotterdam – Dutch municipalities – national and regional media – educational and healthcare institutions – Kellerman Bureau in Actie – Rodi Media – Zuyd Vertalingen – Imagebuilding – NNID – COC Netherlands and regional COCs – Matchingsfonds – Fonds BJP

…and above all, by all the beautiful, strong, and courageous people who, with their personal portraits and stories, want to set an example in coming out with their intersex experiences.

For more information about the exhibition, magazine, podcast, impact program, please visit www.stichtingopenmind.nl/intersex.

#intersex 1 in 90

Project by Open mind foundation

Support the Open mind foundation

The Open mind foundation connects and strives for a society in which everyone is seen and heard. Its goal is to place social injustices, abuses, and prejudices in a different light and make them discussable. Open mind does this by bringing complex issues to the attention of the general public through the realization of artistic projects and by telling relevant stories in the public space. We can’t do this alone. Support the Open mind foundation, privately or as a business expense, and contribute to a more open-minded society!